With this eleventh installment, Prose Editor Kawika Guillermo continues “Stamped: Notes from an Itinerant Artist,” a travel series focusing mostly on art, literary exhibitions, and “artist areas” around Asia (and perhaps beyond).

Note: The views expressed here are entirely the author’s own and do not claim to represent those of decomP.

On Trump and Colonial Travel

I was on an airplane when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. When we landed in Hong Kong, I was so sure that “H” had already won, that when I saw my friends turn white from reading their phones, numbed by the news, I thought a bomb had dropped. I recall the faces of those around me–the Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese, coming direct from Vancouver, Canada, each one speechless, as if the light from their phones induced them to silence. Then I looked forward, to the first class and business class cabins. There was a group of Westerners, silent not from shock, but from trying to conceal their smiles. One of them, a man in a dark blue blazer, stood up straight and closed his eyes, straightening his body in place as if to keep from jumping for joy.

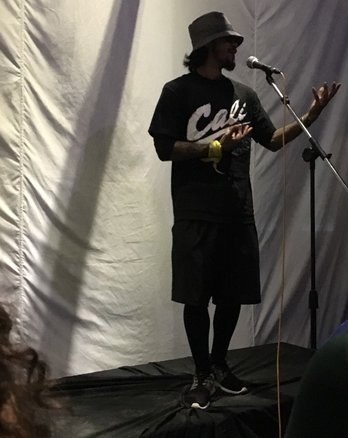

Four days later, I saw what lied behind these smiles at an Open Mic poetry reading in Central, Hong Kong’s old colonial district. A dark-skinned poet from Canada read a poem about his deep sadness after the election. Immediately after, an outraged man (white) spoke on stage, shouting that we needed to respect Trump and his wife–since she knows four languages, he pointed out–and “Fuck you” to anyone who writes badly of them (his finger pointing to the previous poet). The Open Mic became a literary war zone. A young woman (Asian, diasporic) took the stage with her personal poem detailing her fear and hope for the future after Trump. Then a man (white, American) asked his Russian girlfriend to go on stage and read his poem, which included the phrase “I was chatting with this chink from Vietnam,” and ended with complaints about how American women were too fat and Asian women were just right. A friend of mine, a visiting poet, asked me if it was appropriate to kick his ass.

It took me two months to fully process these reactions to Trump’s election. Even as a travel writer, university professor, and teacher, I have never been able to let go of the notion that travel, and living overseas, can make you a better person. Better at understanding different cultures. Better at appreciating different ways of life. Better at loving those around you. But for the past year, since living in China and Hong Kong–and since beginning this blog–I’ve come to the opposite conclusion. Travel, if anything, makes you more certain of the prejudices you have. It couples your ignorance of others with the certainty that you already know everything about other cultures, and that they are just as despicable as you are.

Sound too dramatic, too simplistic, too reactive? Fine, I don’t mean that everyone who travels becomes a bigot. But those who travel, particularly those who write and talk about their travel experiences, often do so with the clamor of a medieval knight errant spouting tales of how they rescued a local damsel from the evil barbarians.

OK, so I don’t mean all travel writers. I have in mind a type of travel writer, the new colonial writer, represented in one particular author–C. G. Fewston, an expatriate author in Hong Kong who claims to have been nominated for the 2016 Pulitzer Prize and the 2016 PEN/Faulkner award for a novel, A Time to Love in Tehran, (evidence on both of these claims has been entirely absent, but I invite anyone to assist in fact-checking). Not long after Trump’s election, I got into a Twitter-spat with this author when he started trolling the writer Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of the actual Pulitzer Prize nominated (and won) novel, The Sympathizer. Nguyen is a Vietnamese refugee, which Fewston (who has lived in Vietnam) sees as a reason to disqualify him from the Pulitzer:

As an admirer of Nguyen’s work since I was a graduate student, I responded to this stream of tweets with deserving vitriol:

This was enough for Mr. Fewston to ban me from his Twitter account. In time, however, I began to get word from fellow Hong Kong writers that this author was “at it again,” posting a slew of tweets against Nguyen, Junot Díaz, as well as refugees, immigrants, and people of color generally:

I won’t bother dissecting these piece-by-piece, except to say that Mr. Fewston is clearly one of thousands of American expatriates in Asia emboldened by Trump’s wall, Trump’s refugee policies, Trump’s white nationalism. It isn’t Mr. Fewston’s political position that interests me, but his means of using travel itself to legitimate anti-immigrant rhetoric that masks itself with “#love,” and with his own standing as an immigrant in Hong Kong. His knowledge of Viet Kieus is deployed to name a refugee as un-American, and if you disagree, it’s because you don’t know what a Viet Kieu is (he will educate you). His knowledge of “Vietnam’s Civil War,” as he calls it, erases America completely from the picture. His self-named “travel writer” position allows him to spit this nonsense while claiming to be “apolitical” (the haven for those whose politics ally with no communities or peoples). His travels give him an enlightened “worldview,” which others cannot begin to comprehend, trapped as they are in their American racial identities.

We are all familiar with this. Mr. Fewston’s travel is the type of travel of the colonials, old and new; of the traders who once worked for the East India Company but now work for J. P. Morgan; of the religious zealots like Marco Polo who now seek to rescue Asians from themselves (especially beautiful female Asians); of the travel writers who created barbarians and cannibals and who now write of exotic women and tyrannical Asian men. These travelers have always used comparisons to justify hate. They see hate and bigotry in other countries, regard it as a fact of life, and see racism in the U.S. as no big deal.

How to Travel like a Colonial (Hint: You’re Probably Already Doing It)

There are many ways one can travel. But in the 21st century, like in the age of colonialism, imperialism, and chattel slavery before it, most travel routes are fixed to make Westerners more certain in their own prejudices. Industries of tourism, English-language learning, and colonial enterprises have set-up travel as just another scheme to reward arrogance. And in an era of identity politics, when we all want to be minorities, it’s a way for the most privileged among us to have their own stories of prejudice to tell.

I’m a traveler of sorts, and I’ve heard the same rant from white Americans in every major Asian city, from #Seoul to #Shanghai to #HongKong. It’s the “we are the minorities now” rant, where Westerners fantasize that they are being harmed just for being white. At a time when immigrants and refugees are under attack in the U.S., this takes on a particularly sinister form of colonial arrogance. Claiming that because you were an expatriate in South Korea you know what it is to be a minority in the U.S. would be like taking a tour of the Grand Canyon and claiming that you really know what life is like “living on the edge.”

But the white colonial experience in Asia, as much as some of us would like to believe, is not the same level of social integration expected (demanded, forced) as a Muslim refugee in the US. It’s not even “same same but different.” Sure, you may have suffered loneliness (even among the women available), you may have suffered time (filling out multiple Visa forms), you may have suffered financially (paying double taxes), but think–are these anywhere similar to the terrors of the police, the FBI, the lynch mobs, the courts, who have always protected majorities over minorities? Were you ever vulnerable to an omnivorous prison complex targeted at you and your family? Were you ever told to change your religion, your values, your language?

In the age of identity victimhood, travel can offer everyone a part to play. No wonder the most privileged of us obsess over the types of travel that offer instances of fabricated danger–in camp sites, in tourist cities of Thailand, China, Cambodia, in music festivals, in clubs, in casinos, in drugs. We embrace these moments as memories of “risk,” when really we were no more taking risks than a family visit to Disneyland. We pretend that after wallowing in a hostel in India we are suddenly equal victims as those black bodies living on the streets of Baltimore, Washington D.C., or Detroit. We get food sickness and pretend we can now understand the dysentery plaguing the starving. These attitudes bring us no closer to those we now claim to understand, but merely widen the gulf with our newfound arrogance. And in that arrogance we go on, guilt free, back into the dream made for everyone and no one.

Some of these colonial authors will use stories of pretend oppression to fold back into protecting their American heritage. They will insist that Americans join the rest of the world in racist exclusions. They will see how Koreans protect Koreanness, Japanese protect Japaneseness, and our writer in turn will move to protect Americanness as a white cowboy Christian mythology. They will say, straight-faced, that if Asian countries can protect their mythical national race, why can’t we? Victimhood, migrancy, historical marginalization–these are mere games for these players, these movers, these managers, these writers, these travelers. But the pieces locked into the board are not playing along.

The biggest question for the traveling writer is not about the space itself but why we are inhabiting it. You the American traveler, who came armed with the world’s highest-valued passport, who could afford to burn cash and jet-fuel on a prolonged vacation, you who reside in a land that belongs to others but has been ready-made for you, with a job just for you, an inhabitance just for you, and people willing to risk social stigma just to spend time with you. What are you doing here, really? What do you hope to take from this place, really?

Self-Tourism

Travel can expose the dark sides of the world, so it is natural that it can make us more prejudiced. By being exposed to atrocities, we can walk away believing that, by acting on our prejudices, we are merely matching the prejudice of the rest of the world. Yes, there is racism, bigotry, and hate in every country. But there is also protest, struggle, and organized resistance. In every country you will meet those who are part of the struggle for justice, whether they are trying to impeach a president (as in South Korea last year) or are writing editorials that will make them targets for censorship and state violence (as in China, the Philippines, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia). And in every country there are those who see hate everywhere, who have traveled just to come back and say “they do it over there, so why can’t we?”

For those of you living in America, who see the writings of colonial travelers and say, “at least they’re not in the U.S.,” I have a wake-up call for you. These travelers and expats, who might be LBHs (“losers back home”), are well respected in Asia. Many of them are educators, entrusted to represent American history, culture, and politics. They are “young professionals,” poets, writers, artists, intelligentsia. Now, with the election of a man who seeks to rid the U.S. of non-Christian, non-Western elements, they are emboldened. They seek to represent America’s voice to the world, as expert travelers of the world. And here, people are listening.

The ferry skids along. I return to sit with the Filipina Americans, smiling kindly at the Filipinas sitting across the bench, unsure what kind of gestalt inspiration we’re supposed to be getting from them. But the Filipinas don’t stare. They all have 3G internet. So the Americans stare at the Filipinas staring at American music videos, each of us, perhaps, trying to put this lack of feeling into words.

The ferry skids along. I return to sit with the Filipina Americans, smiling kindly at the Filipinas sitting across the bench, unsure what kind of gestalt inspiration we’re supposed to be getting from them. But the Filipinas don’t stare. They all have 3G internet. So the Americans stare at the Filipinas staring at American music videos, each of us, perhaps, trying to put this lack of feeling into words.