With this ninth installment, Prose Editor Kawika Guillermo continues “Stamped: Notes from an Itinerant Artist,” a travel series focusing mostly on art, literary exhibitions, and “artist areas” around Asia (and perhaps beyond).

Art Spaces in Phnom Penh

Spoken Space

We (you and I, let’s say) stroll along Street 308, an “up and coming” (read: gentrifying) area of Phnom Penh, speckled with packs of foreigners and tourists armed with open-carry bottles of wine and thin needles of hash, their bodies attached to tall resident walls like seaweed wavering to and fro against a stream. The street directs us to the dawdling Mekong river that flows from southwest China, bordering Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, before drifting through Phnom Penh and into Vietnam.

But the street comes to an end at Cloud bar, a “unique culture, art and music venue,” according to the googlemaps reviews I looked up, which also recommend the “excellent homemade punch.”

We squeeze into the back row of a shark-fin shaped room, where Kosal Khiev, the renowned refugee spoken word artist, will perform. A refugee to America at one year old, tried as an adult at sixteen for attempted murder, imprisoned for fourteen years, and at thirty-two, named an “alien” and forcibly deported to Cambodia, Kosal’s very survival is stunning. That his heart still beats after so much pain, that his mind still functions after fourteen years in prison, that his head still holds high after eight months in solitary confinement. That he’s not only here, but that he exudes a force both calming and energetic, alluring yet visceral.

One of Kosal’s students, Conrad, introduces him as a survivor: “He was one of the survivors of the Khmer Rouge, he was a survivor of the war, he was a survivor of freedom, of the American dream, whatever you want to know, he is a survivor of violence, more importantly he’s a survivor of the system.” Conrad mentions Kosal’s community work, too long to list for a simple introduction. What comes first? His mentorship of young artists? His work with Cambodian children? His national stardom at the 2012 Olympiad? His starring role in the documentary Cambodian Son? In a city that has become a symbol of survival, he is its offspring.

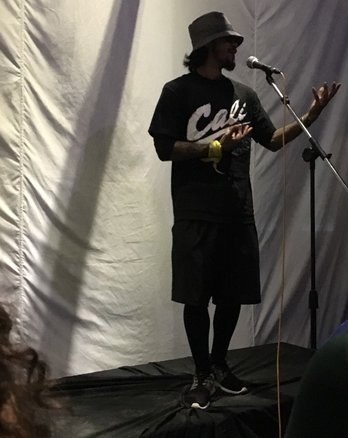

Kosal takes the stage. He’s a scrawny man in a black hat and black T-shirt. He makes room for himself, removing the microphone stand, the lectern, the chairs, forcing a circular space where he can spread his tattooed limbs. Then the words flow out of him in a soulful song, “I’m on a midnight ride on a rail of a beaten down trail / I got my hat down low and I just made bail,” then the words push us down, submerging us, his rhymes splitting us against a barnacled floor more shallow than we could see from above:

call me a murderer, a homicide, I just died by a pack of wolves dressed up as the uniformed service, a flock of crows purposefully moving with guilty verdicts, executing and shooting anyone moving with purpose.

Kosal lunges out, hands shaped like glocks towards the sky, words charging in bullets. His face captures us, dense in desperation and prayer, wrinkled from an age apart.

Dancing Space

It’s Kosal’s face that haunts us as we jump into a tuk-tuk towards the weekly drag show at Blue Chilli’s bar. The show has become a ritual jaunt in Phnom Penh, an event that pleads to us more than the killing fields, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, the markets, the river itself. Speaking of: our driver follows the Tonle Sap river north, against its stream, passing hand-in-hand pedestrians, jostling youth, and women exercise-dancing near the river walk. I watch the water’s unstable darkness and remember there is a drought in Cambodia’s countryside. The worst in fifty years, the dry wind and dust has left tens of thousands in need of water and food.

Naked colored bulbs welcome us into a rectangular bar overflowing with alcohol. We watch the queens slam things into the ground: their heels, their asses, their wigs. We drink and shout to new friends over loudspeakers. We duck below coiled wires leading to electric lights. We grip each other, facing the dancers like flags fluttering in trade winds.

Miga, the queen of Blue Chilli, takes the stage with a looming intensity. Her eyes flutter. Her body seems weightless as she breezes up and down a silver pole. Like Kosal she wears black–black dress, black bouquet. You spy something odd about her hat–not a hat, but a revolver, held onto her hair like a perched bird. We can’t help but gawk at it–a symbol of American cowboys, of violence, whisked easily into a drag queen’s ornament.

Like Kosal, Miga has been a community pillar. The amount of events she headlines, teaches at, and supports, is a testament to what the “community artist” can really do. Her pride in drag coupled with her unstoppable talent and energy has made her a powerful symbol for the LGBT community. She is a drag queen who has appeared on national television and hosts fashion events. Her makeup tutorials have brought her to issues of wildlife (The Jungle Project), and her fem performances have brought her to breast cancer awareness groups. Given this dedication, it’s no surprise that she has also been violently attacked in clubs by, as she calls it, “people who hate sissys.”

After Miga’s performance, we share a dinner with her, now going as ‘him.’ He says he’s never met Kosal Khiev. We ask if the two worlds collide–one of spoken word American exiles, the other of queer Cambodian revolt. Perhaps it’s a sign of my American-ness that I see them as part of the same project, both of them upending the tired, toxic tides of masculinity. They fire not with bullets, but with words and make-up. Their audiences may be separate, but they’ve both become symbols of hope, having lived through hardships that, in the West, are often summarized on the back of a memoir’s book-jacket. And their talent has to be seen to be believed. It makes me wonder what happens to less talented artists in this city. Surely, many had gone lost while trying.

As we talk to Miga, I notice he never uses the word “survive.” He explains himself without this word. He has no lovers, but loves only his passions, his community work, his performance art, and his full time job as a barista. All of this, and he never makes it sound like a struggle. These things bring him life. It’s not merely a way to survive–but to survive well, to inspire, and to exclaim: “We are here.”

—

Prose Editor Kawika Guillermo spends his days traversing around Asia, with Hong Kong as his beloved base. His fiction has appeared in Feminist Studies, Drunken Boat, Tayo, and The Hawai’i Pacific Review. His debut anti-travel novel, Stamped, will be published in Spring 2017 by CCLaP Press.

Tags: Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Stamped