about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the novel Here Is How It Happens (Ampersand Books, 2013), the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), the chapbook Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

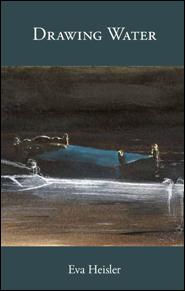

A Review of Drawing Water

by Eva Heisler

Spencer Dew

I am living by Lake Michigan, and in the early mornings I go out, under the overpass and over the bike path, down through the cuts in the tall grass by the cinder-block circle at Contemplation Point, onto the sand at a beach named for someone who, if I have the story right, died of cancer. Of the things to study there are the behavior of gulls, the gradual lessening of dependence from the juveniles, their cries; the meditative and exercise practices of certain elderly Slavic and Asian men, barrel-built, sun-puckered; and the horizon, that almost illusory real, paper-sharp at points, or dissolving in a haze and shadow, flickering with the thousand-thousand wind-swept diamonds of the water’s surface.

What does it mean to do the sky tenderly, or acquire some sense of feeling from the shades of black certain painters employ—the nuance that is Goya’s black, or Reinhardt’s black, that “is not black but yellow and sometimes purple”? At what point is criticism poetry; at what point is one thing something else? Consider: drawings that “consist of a build-up of delicate cross-hatching. Each drawing takes up to two weeks to complete, the result of thousands of measured strokes.” Or this miniature narrative: “My daughter recalls waking from a nap when she was seven and knowing by the way the sun hit a calendar on her bedroom wall that she has slept a long time. ‘I remember feeling sad because seeing all those days made me think I had lost one of them.’” Follow the associational flow and consider how a desk diary structures time: “Time no longer dissolved like sugar in water but hardened / like gum stuck to the secret blue beneath // a table top.” The Proustian is inexhaustible. We are not talking about concepts, exactly, when we remember smells or describe patches of color. Chalk dust as representative of a state of mind; negative space rendered visible by recognition, perception keyed to expectation, to knowledge, to desire.

Hierarchy hides in every taxonomy; not only is the economy of art-as-project defined by labels and categories, this system of assigning to slots is also always a political move, colonizing, marginalizing. See how the bookstore gets sorted, the formal niches and subgenres. “Urban Literature,” for instance, is given a special display at my branch library; “Gay and Lesbian Literature” has its own nook. “Poetry” gets filed with “Plays” and “Memoirs,” oddly, whereas “Literature” means novels and story collections. These are issues which Noctuary Press was founded, in part, to address, to open conversations about; this and the publishing of hybrid work, the hard-to-define, intentionally wandering the borderlines between standard forms.

I stop by the Art Institute some days, on my lunch break, and there are often classes of some sort, adult education, continuing or whatever they call it, in certain upstairs galleries sketching and painting versions of the classics. Of the most interest is how the Turners are treated, the avalanche and sea-borne storm, violent slashes of rain, the clouds like lost-wax casts of caves, the curve and crash of raw and self-illuminated color in all the hues of subtle light and intimate bruise. Contusion and candle flame, with weather streaking itself from allegory into abstraction. Some students concentrate on the shepherds huddled in the far corner. Some see past the sky to some vast idea, the horizon pried open, spread wide.

“Take any narrow space of evening sky, between branches, or between two chimneys, or through the corner of a pane in the window you like best, and try to gradate a space of white paper as evenly as that is gradated—as tenderly.” The ghost of John Ruskin. Advise for aspiring artists, because we listen to voices for models for and of ways of seeing and being in this world. “I work with little ink in my pen and hardly make a mark,” says a voice here. The page as a landscape, white space and faint but determined marks. Cross-hatching over an expanse. Days of effort to achieve a wash, a slight alteration in tone, a mimic of a shadow. Another voice: “I waved the draft of a poem up and down. We watched as a gleam of light struck my left hand each time the white paper passed over me.” Signaling for some distant watcher. “I spend much of my writing time seeking the horizon line.... I look up from small blocks of text and squint at the sea. To write prose poems is to resist the horizon line—.”

You know that one video game, where you drive a tank, the barest outline of a tank, little more than a tetrahedron, an outline of an implication of a carapace, metal, loaded with shells. And there are mountains and obstacles, mines, enemies of various vague sorts, which, when hit right, explode into flat paneled fragments. But what dominates the gray and green screen is the horizon line, that flat demarcation, rippling at times like a heat mirage. As fast and as hard as you push in the same straight line, the horizon recedes equally to your efforts, remaining always ungraspable, a measure not of distance but of scale, not the geographical but the mortal. That line says something about who we are. Our interactions with it offer our most authentic legacy.

Official Noctuary Press Web Site