about the author

Staff Book Reviewer Spencer Dew is the author of the short story collection Songs of Insurgency (Vagabond Press, 2008), Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Another New Calligraphy, 2010), and the critical study Learning for Revolution: The Work of Kathy Acker (San Diego State University Press, 2011). Dew is also a regular reviewer for Rain Taxi Review of Books. His Web site is spencerdew.com.

To send your new book to decomP for possible review, see our guidelines. To find out what’s currently under consideration, visit our review queue.

∧

font size

∨

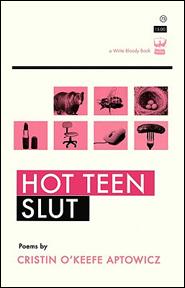

Reviews of Dear Future Boyfriend, Hot Teen Slut, Working Class Represent and Oh, Terrible Youth

by Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz

Spencer Dew

Reviews of Dear Future Boyfriend and Working Class Represent

Sweet poems about parents, childhood, and striving...scrappy poems about used clothes, coffee stains, and the drive to write...poems that pluckily declare their own origin in the cubicle or the sad but industrious subway car—Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz makes hard seem too easy, like life itself just squeezes out of the toothpaste tube in the shape of a poem, like poems fall out, ready-made, from between the pages of old National Geographics the way maps used to and maybe still do. But who has time for maps when there are so many poems detailing movie musical fantasies, dreams of murdering ex-boyfriends, or the quest to find a corporate sponsor for the loss of one’s virginity?

Not that you need elaborate choreography for an Aptowicz poem; one, entitled, “Too Many: Twice” reads, in full “This is the ratio of the number of poems / I’ve written about you to the number of times / you’ve called me back.” Does this writer ever sleep? The evidence points towards yes, because between the poems about hotel sheets and cold medicine there are poems that deal, too, with sleep. Then there are poems about having poems rejected, poems about performing poetry, writing poetry, finances, and cafeteria food. Then there’s a sharply intimate and unexpected piece about 9/11, a poem featuring a speaking beaver in an ascot and smoking jacket, even a poem with some Klingon in it, somewhere, and one that makes mention of SweeTarts, which is perhaps an apt metaphor here, because these two books are chock full of tiny, tangy confections, and while you might read a review, like this one and think, ‘Really? A poem about writing a poem on the subway?’ you sure don’t know the recipe, or you would write books like this for yourself, because they are that good.

A Review of Hot Teen Slut

“It’s important to remember: there should be porn / on your screen.” the narrator’s new boss tells her in one of the earlier poems in this narrative collection, almost a novel-in-poems, chronicling a brief career working a desk job for the porn industry. Beginning with a poem about the job ad, a poem about the interview, a poem about the first day, this is a book that tells a story with absurd edges but an all-too-relatable core—a young poet “in a country / that only spends 4 cents per citizen on the arts” has been reduced to living on “frozen pierogies / and day-old pastries scored for free” and catches the Internet boom in its last staggers. These are days of office foosball tables and free Pop-Tarts. Oh, capitalist youth! Fantasies for sale! Yet our narrator is both savvy and sassy, far from blind to the political implications of the industry, she’s simultaneously so good-natured, so full of verve and a near-utopian vision of pleasure, that instead of a book all about tearful gagging, bruised faces, and triple penetration we have a book that’s willing to offer, in defense of its own arc,

And yes, sometimes I come across things that are ugly and cruel, things that validate every terrible thing that porn has to offer. But I feel like I have an opportunity to help the beautiful and the empowering to kick down some doors.

I feel like I can liberate porn from its five-hundred-cocks-in-one-night, bad-boy status, and show the world that porn can be fun, that it should be fun, that it is fun. That some days we should all get naked, accidentally cover ourselves in milk, wrinkle our noses and smile, simply because we are the most beautiful people we know.

Some will surely say this is naïve, especially as musing supposedly triggered by a passing pedestrian’s objectifying aside and considered along the plight of a friend who, far from the safety of the air-conditioned cubicles behind Internet porn, makes a living off tips, “bending at the waist as specifically spelled out in the Hooters Handbook,” which goes on to make other draconian—and far from culturally isolated—commands on its employees, its pantyless “girls.”

But this isn’t a book about the pornographic imagination, the pornography industry, or even about gender relations or asymmetrical sex. Not really, jibes against the “titty-fuck” aside. This is a heartwarming book about a young woman with moxy and hunger and a refreshingly optimistic view of the world that doesn’t get dampened by a job that is, remarkably, strange and tedious in ways that make it a gorgeously hyperbolic metaphor for everyone else’s strange and tedious cubicle jobs. And, let me be clear, this is a book of poetry about a poet, a Bildungsroman with Internet porn taking the place of, say, the old Grand Tour of Europe and its galleries. Here is a poet who can observe, deliciously, “Porn / without a cum shot / is like a sestina / without a BE/DC/FA / concluding stanza” and can compose a sestina of her own from lines of porno pop-up ads (whence comes this book’s title). “I bet people ask you a lot of dumb questions, right?” begins a list-based pantoum titled “Questions Boys Ask Me About My Job.” In a handful of other pieces, the poet ponders what it would be like if, by decree, worn words were replaced with other, fresher coinages. What if “tampons” were called “power rods,” for instance, or “semen” suddenly became “Gay Power Spray”? The poet gambols through a flight of linguistic fancy: “Baby, I’m going to pull out / and spray Gay Power Spray / all over your boobs.” Maybe some people will laugh harder at some pages than others, but anyone even remotely acquainted with Google’s history-based prediction system will find delight in lines like

Still, when your mother remembers

reading an article in the New York Times

about a place in Queens that sells

The biggest, hottest sausage in NYC,

you have to ask her to step away

from the Google search box...

That this collection of pieces around work in pornography can be so heartwarming, not just funny and not just smart, is itself a victory; poetry wins in this book, and readers will find themselves cheering it on. Even if the background is thick with grunting, glory holes, etc. As the narrator of an early poem says, “Everything is beginning to look / a little strange to me now.” And yet some of the strangest stuff looks completely familiar, known. Which is precisely what poetry is supposed to do. Even a letch’s sneered appreciation of your tits can become something beautiful, a manifesto for beauty itself. Go poetry! Like I say, it will leave you cheering.

A Review of Oh, Terrible Youth

Poetry as a return to childhood—an old theme, yet solid and expansive, implying wonder and hindsight, innocence as viewed by the experienced...some nostalgia, perhaps, but balance by equal parts clear-sightedness. Aptowicz, rapidly distinguishing herself as one of our sunnier young poets, is clearly at home here, even or perhaps especially in the midst of the most cringe-inducing memories. Yet for all the “Elementary School Confessions,” and awkward, homemade Halloween costumes, this book isn’t about the embarrassments of peeing oneself or the hyper-self-consciousness of junior high dances or the angst of prison-sentence days of late adolescence wasted in school. Aptowicz, rather, celebrates the “Determined denial” that accompanies the rough-and-tumble Ewok costume (“Bristly doormats tied to chest and back with twine / Grandma’s fuzzy hat”) in which she’s equipped one holiday, relishes her role as a tangential guest at a Star Trek-themed bar mitzvah (seated at the table labeled “Klingon Ship #2”), and sings of the radical possibility of teenage freedom, the infinite horizon of the future as viscerally encompassed in the feel of driving off by yourself, those times when “the radio feels like a soundtrack // and the radio feels like an anthem.”

So alongside funny list poems about siblings and English class, pale beach vacations and “The Absolute Worst Games of Childhood” (“Clean-Up Robot” and “Let’s See Who Can Be the Quietist” make the list) we’re also offered some deeply moving engagements with memory, its persistence and how it fades. “But now, I could form a terrible band / with all the boys” whose names the forgetting of which would, once, have been unimaginable, one poem tells us, while others reflect on friendship, the changing dynamic of how we imagine the future as we rush or plod off into it. There are notes of regret, of loss, a recognition that in life, as apart from art, “closure” is “the itch you’ll never reach.”

Yet while old friends might have wandered down other, duller paths, the narrator of these poems reinvents her world, over and over. The reliving of childhood pleasure is, of course, a new experience, categorically different from the original living with all its stress and unknowing. Going trick-or-treating with the neighborhood dads, “an open Budweiser keg ... dragged around behind us,” means something different now, as does how the tangled complexity of how back then, “For a whole year, I made fun of a kid because his lunch mat / showcased the brief biographies of every U.S. President, // despite the fact that I had a proximity-based crush on him, / and that honestly, I’d kill to have that lunch mat now.” There are poems here about crayon colors and the seductive smells of autumn, specifically those weeks straddling two months that a friend calls “Septober,” and the poet terms “The Brunch of Autumn, or the impossibly crisp / Heart of Fall.” This is a book to savor the way we savor certain memories, best characterized by a prayer for prom nights that ingeniously segues from kitschy humor about corsages and parents and cars to an expression of real heart in wise hindsight. Lord, the poem asks, grant

that we recognize the unconscious beauty of youth,

that we feel the fleeting heat of a slow song,

that we listen to the soft hum of the present,

that we see our future, with its hand out, impatient,

but choose to hold on and dance a little longer.

Official Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz Web Site

Official Write Bloody Publishing Web Site